By Nancy Heywood, Collections Services

Last fall, as the Massachusetts Historical Society planned its current exhibition, The Private Jefferson, an interdepartmental team of staff members successfully pursued a wonderful opportunity to incorporate technology into the galleries. Thanks to the efforts of Gavin Kleespies, Director of Programs at MHS, and Ryan Gaspar, Director of Strategic Partnerships, Microsoft, MHS staff members were able to showcase MHS digital content in an interactive content management system for exhibitions, Touch Art Gallery (TAG). Numerous high resolution digital images, short videos, and interactive features are available on a variety of touchscreen devices within the Jefferson exhibition.

TAG was developed by a team of programmers (mostly undergraduate computer science students) at Brown University led by Professor Andries van Dam, the Thomas J. Watson Jr. Professor of Technology and Education. Carolyn Gress, Marketing Project Manager, Microsoft, coordinated a meeting in October between some staff from the MHS and Professor van Dam and some of his students. During the visit to Providence, Rhode Island, MHS staff saw and interacted with the digital museum experience they created using TAG for the Nobel Foundation.

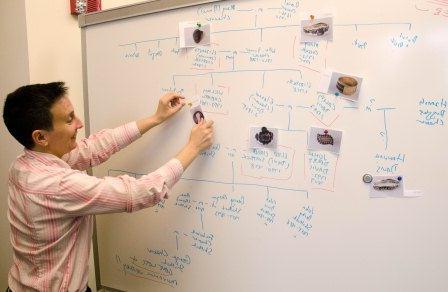

Notable features of the TAG system include: the display and delivery of high resolution images of exhibition items and their associated metadata in various sets (“collections”); management of related material including audio and video clips; and interactive segments on topics (“tours”). Gallery visitors can browse the items, “grab” and zoom in to closely examine the high resolution digital images, select, start (and interrupt) the interactive tours to closely examine the featured images.

Due to several previous grant-funded digitization projects, MHS has many existing high resolution digital images of documents within the Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts. These digital assets and the existing metadata were good starting points for the implementation of TAG within the Jefferson exhibition, but it took intensive work and effort by many staff members to ready the digital features by the opening date of the Jefferson exhibition.

The digital team (Laura Wulf, Peter Steinberg and I) had to work efficiently to assemble over a hundred images and descriptions. Bill Beck, MHS’s web developer, worked with Trent Green (the Brown University student who our main contact for TAG server and software issues) on the batch ingest and overall configuration of the system. Several staff members (Gavin, Sara Sikes, Sara Georgini, Peter Drummey and I) focused on the content for six interactive features and developed outlines and scripts to tell specific stories about the Jefferson materials. The production of those interactive tours was truly a team effort with Gavin and Bill taking the lead on many sequencing and editing tasks; the digital team assembling more images; Sara, Sara and Peter providing narration for some tours; and Jim Connolly and Hobson Woodward recording additional audio clips. Three staff members, Chris Coveney, Carol Knauff and Laura Lowell, provided excellent feedback regarding the multimedia overviews (the “tours”).

The digital content and the touch screens of various sizes–ranging from one large (65″) screen to two Dell All-in-Ones and one Microsoft Surface tablets–had to be physically incorporated into the exhibition. Gavin worked with exhibition designer Will Twombly and MHS’s Chris Coveney to ensure that the screens were accessible and functional in the gallery spaces.

The digital content and the touch screens of various sizes–ranging from one large (65″) screen to two Dell All-in-Ones and one Microsoft Surface tablets–had to be physically incorporated into the exhibition. Gavin worked with exhibition designer Will Twombly and MHS’s Chris Coveney to ensure that the screens were accessible and functional in the gallery spaces.

The result of so many people’s efforts with the planning meetings, the configurations, the production tasks and deployment steps is an exhibition celebrating MHS’s 225th anniversary with significant historical manuscripts (the core of the collections) as well as value-added digital content on current touch-screen devices. We strived to make the digital content as informative and user-friendly as possible.

Please visit the Jefferson exhibition to examine both the original manuscripts on display as well as the digital components on the touch screen devices in the galleries. Professor van Dam and some of his students will be giving a gallery talk about the development of the Touch Art Gallery system on Friday, May 13, at 2PM.

Image: Screenshot of a tweet Liz Loveland sent during the Jefferson exhibition opening with an image of a manuscript page from the Farm Book delivered on a touch screen device.

had their own ways of commemorating loved ones. In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, an upcoming exhibition at the MHS by jeweler Sarah Nehama and MHS Curator of Art Anne Bentley, examines the practice from the 17th through the 19th century of commissioning and wearing rings, bracelets, brooches, and other jewels to honor the dead.

had their own ways of commemorating loved ones. In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, an upcoming exhibition at the MHS by jeweler Sarah Nehama and MHS Curator of Art Anne Bentley, examines the practice from the 17th through the 19th century of commissioning and wearing rings, bracelets, brooches, and other jewels to honor the dead. available for purchase on

available for purchase on

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.