Native American Photos

Photographs of Native Americans

Unidentified girl standing with bowls

Unidentified girl standing with bowls

Unidentified man holding pipe tomahawk

Unidentified man holding pipe tomahawk

Unidentified woman leaning through window of adobe building

Unidentified woman leaning through window of adobe building

The portraits in this web presentation were collected by four Bostonians during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Charles W. Jenks and Francis Parkman collected carte de visite and tintype portraits of Native Americans from the central and western parts of the United States during the 1860s as historical records of tribal groups and their role in contemporary American politics. After a visit to southern California, Boston collector Kingsmill Marrs brought home platinotypes of southwestern peoples taken by Adam Clark Vroman in the late 1890s. An anonymous donor was inspired to collect Joseph Kossuth Dixon's photogravures from the Wanamaker expeditions of the early 1900s after hearing Dixon lecture in 1912.

Early portrait photographs of Native Americans, similar to those presented in this web exhibition, reflect a widespread public interest in indigenous life during the 1860s. In the mid-nineteenth century, the popular carte de visite photograph introduced the faces of prominent public figures into homes across America. Easily mass-produced, uniformly sized, and cheaper to purchase than early cased photographs, these portraits were collected, in part, as a record of current political and social events and of the people who drove them. Patented by French photographer André Disdéri in 1854, cartes de visite were introduced to the United States in 1859. The craze for these photographic "calling cards" took off in the 1860s, leading Oliver Wendell Holmes to write in 1863 that "card portraits ... have become the social currency, the 'greenbacks of civilization.'"

These striking images of Native Americans depict the changing ways in which photographers portrayed them during the latter half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. From 1860, when the first portrait in this collection was taken, to 1913, the nation experienced unprecedented growth and American settlers claimed lands inhabited by indigenous people. These images are attempts by photographers to document what they saw as the fading of Native American cultures and traditions, to illustrate periods of conflict between the U.S. government and the tribes, and, by the twentieth century, to evoke political sympathy for the cause of the "vanishing race."

Please note that this web presentation and its associated item records contain outdated creator-supplied language and discussions of violence.

Funding from the Richard Saltonstall Charitable Foundation supported this project.

Chippewa man and unidentified man, possibly photographer, Charles D. Fredricks, in Washington, D.C.

Chippewa man and unidentified man, possibly photographer, Charles D. Fredricks, in Washington, D.C.

Man holding rifle, identified as Spotted Wolf

Man holding rifle, identified as Spotted Wolf

Two unidentified men

Two unidentified men

Early Portraits of Native Americans

During the late 1850s, the development of glass plate negatives and paper photographs made photography a more commercial—and thus more public—enterprise. Photographs were used not only as private commemorations of a particular sitter, to be viewed only by his or her family, but also as a public record of, and commentary on, current events and culture. Beginning in the 1820s, the United States government collected portrait paintings of Native Americans for its "Indian Gallery," as a way to preserve a visual record of peoples that they considered doomed to extinction in the face of western expansion and by the perceived inability of indigenous people to adapt to traditional American culture. As photography became more acceptable as an artistic and documentary medium, photographic portraits of Native Americans superseded paintings as a public documentation of the "vanishing race."

The photographs exhibited here were taken mostly by Plains and Rocky Mountain photographers and depict Arapaho, Cheyenne, Chippewa, Ottawa, Pawnee, Sioux, and Ute men and women. Many of the portraits appear to portray their subjects objectively, wearing representative traditional dress. Others show the ways in which the photographers perceived their sitters in relation to the Manifest Destiny of western migration, posing them in front of American flags or in aspects of colonial American dress. Still others reveal a subtle commentary on the ways in which different peoples interacted with American expansionism.

About the Photographers

Charles DeForest Fredricks (1823-1894) has been credited as the first photographer to introduce the carte de visite format to the United States through his New York studio and is primarily known for his popular carte de visite portraits of eminent Americans, most of which were taken and published during the 1860s. Fredricks began his career as a case-maker for daguerreotypist Edward Anthony of New York, N.Y. (who also became a renowned publisher of cartes de visite) but also learned the techniques of photography from another prominent New York daguerreotypist, Jeremiah Gurney. Hearing of work available in South America for itinerant photographers, Fredricks traveled there in 1843, eventually setting up shops in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, as well as Cuba, during the late 1840s and early 1850s. In 1853, Fredricks returned to New York and entered into partnership with Gurney, experimenting the following year with new techniques in paper photography. He eventually opened his own photography studio in 1857 and continued to work as a photographer in New York until 1889.

William Henry Jackson and his brother Edward opened their Jackson Brothers photography studio in Omaha, Nebraska in 1867, merging it with another Omaha studio owned by William, Hamilton & Jackson's Gallery of Art. That same year, William did some of his first "field work" photography, taking some of the portraits of Pawnee, Otoe, Arapaho, and Sioux men that appear in this web presentation. Previously, he had worked as a photographic retoucher and, during the Civil War, served as a staff artist in the 12th Vermont Infantry. William Henry Jackson would later become the official photographer for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey, led by Ferdinand V. Hayden, from 1870 to 1878; in this capacity, he took what were eventually regarded as some of the most influential landscape photographs of the American West of the nineteenth century. Jackson continued to photograph the West from his studio in Denver after expedition work and, in 1893, was named the official photographer for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The photographs in this exhibition that are attributed to the Denver Photographic Rooms were most likely taken by William Gunnison Chamberlain (1815-1910), a native of Newburyport, Massachusetts who became one of Colorado's most prolific photographers from 1861-1881 and worked for a time for the Denver studio.

C. W. Carter's View Emporium was a Salt Lake City, Utah business owned by photographer Charles William Carter, who founded it in June of 1867. During 1868 and 1869, Carter partnered with photographer John B. Silvis as Carter & Silvis but later returned to his own business. He became a well-known photographer of Utah, its indigenous peoples, and its Mormon citizens. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City holds approximately 1,000 of his original glass plate negatives.

About the Collectors

These portraits from the Massachusetts Historical Society were collected by two Massachusetts men, Charles W. Jenks and Francis Parkman. Charles W. Jenks was a graduate of Harvard College, Class of 1871. He worked in the paper business for L. Hollingsworth & Company in Groton and Boston before settling in Bedford, Massachusetts. There, Jenks's interests included botany, horticulture and agriculture. He served as a trustee of the Bedford Public Library and of the town's cemetery, and was a tree warden and town moderator. Jenks's collection of carte de visite portraits consists of images of prominent American politicians, officers, soldiers, and other public figures active during the years of the Civil War, from 1861 to 1865. Included in these portraits are the two photographs of Chippewa men presented here; these photographs were possibly collected by Jenks to commemorate the Chippewa role in the Dakota Sioux trial of 1862.

The rest of the portraits within this web display were collected by the historian Francis Parkman. Parkman, a graduate of Harvard College, Class of 1844, had studied Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains when he travelled and hunted with the Sioux along the Oregon Trail in 1846. He was a diligent and prolific historian. In addition to writing The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life, he wrote France and England in North America, a multi-volume epic including the titles, The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War After the Conquest of Canada, and Jesuits in North American in the Seventeenth Century, in which Native Americans play a central role. The photographs he collected were taken circa 1860-1871 and depict Pawnee, Ottawa, Arapaho, Ute, Cheyenne, and Sioux people.

Unidentified man in military garb, holding sword

Unidentified man in military garb, holding sword

Chippewa man in Washington, D.C.

Chippewa man in Washington, D.C.

Unidentified man holding pipe tomahawk

Unidentified man holding pipe tomahawk

Two unidentified men holding weapons

Two unidentified men holding weapons

Man holding rifle, identified as Spotted Wolf

Man holding rifle, identified as Spotted Wolf

Chippewa man and unidentified man, possibly photographer, Charles D. Fredricks, in Washington, D.C.

Chippewa man and unidentified man, possibly photographer, Charles D. Fredricks, in Washington, D.C.

Photographing the Sioux

These photographs were collected by historian Francis Parkman and depict the Sioux Nation (Oceti Sakowin), in whom Americans held a particular interest during the early 1860s. Following the Louisiana Purchase, white settlers trickled into Sioux lands, setting up outposts and attempting to intervene in inter-tribal politics. This led to several treaties in which tribes of the Sioux Nation ceded lands to the United States and were forced to move to locations increasingly further from and geographically dissimilar to their ancestral lands. Starvation due to poor hunting conditions on reservations and financial difficulties due to late treaty payments from the U.S. government resulted in mounting tensions between the Sioux people and the United States. In August of 1862, the Dakota (a subgroup of the Sioux who occupied what is now the state of Minnesota) began an armed uprising along the southwestern border of the Minnesota Territory. The 1862 conflict, now known as the Dakota War of 1862, marked the beginning of an ongoing confrontation that would last until the battle at Wounded Knee in South Dakota on 29 December 1890, when more than 300 Sioux people were killed by United States soldiers.

Most of these carte de visite portraits depict Sioux men and women shortly after the 1862 uprising. Some of the images were taken at Fort Snelling, where displaced people were held before the United States Congress called for the forcible removal of all Sioux from Minnesota in April of 1863. It is likely that the photographs of We-no-na (Daughter of Sioux Chief "Red Iron") and tepees were taken in the encampment area connected with Fort Snelling. Harsh conditions at the encampment at Fort Snelling resulted in the deaths of hundreds of people. The photographs of Wo-Wi-Na-Pe (Little Crow's Son), taken in 1864, and Wa-kan-o-zhan-zhan (Medicine Bottle), taken between 1864 and 1865, depict two people who were held by the military as prisoners and put on trial for their actions in the uprising.

The images reveal the conflicted place that the Sioux occupied in the American mind. The subjects are variously portrayed by the photographer as noble victims of American oppression, as curiosities to be visually cataloged before their presumed extinction, or as savages, object-lessons to justify to the American public the government's actions against the Sioux. The captions listed with each photograph were either published by the photographer or written in pencil by the collector or an associate; these captions provide insight into the intention of the photographer toward his subjects as well as the ways in which the images were further interpreted by those who bought them.

We-no-na, (First Born.) (Daughter of Sioux Chief, "Red Iron.").

We-no-na, (First Born.) (Daughter of Sioux Chief, "Red Iron.").

Wa-kan-o-zhan-zhan, (Medicine Bottle.)

Wa-kan-o-zhan-zhan, (Medicine Bottle.)

Sioux Dandy

Sioux Dandy

About the Photographers

Most of the photographs of the Dakota in this exhibition were taken by Benjamin Franklin Upton (b.1818), originally of Maine. Upton made his living as a photographer in St. Anthony, Minnesota from circa 1855 through the 1880s. Many of his original negatives are held by the Minnesota Historical Society.

Other photographs in this series were taken by Joel Emmons Whitney (1822-1886) of Whitney's Gallery in St. Paul, Minnesota, who photographed from 1851 to 1871. Also born in Maine, Whitney was the first photographer in St. Paul, Minnesota, and began working first with daguerreotypes and then as a wet plate photographer. During the early years of the Civil War, Whitney photographed many Minnesota volunteers and also sold cartes de visite of Minnesota Indians. After the Dakota War of 1862, there was great public demand for photographs of the principal participants and Whitney made available many of his images of the Dakota as well as of the United States soldiers who suppressed the uprising. He is considered one of the most eminent early photographers in the United States. He additionally worked as a merchant, miller, and a banker.

About the Collector

The portraits exhibited here were collected by the historian Francis Parkman. Parkman, a graduate of Harvard College, Class of 1844, had studied Plains Indian life while travelling and hunting with members of the Sioux Nation along the Oregon Trail in 1846. He was a diligent and prolific historian. In addition to writing The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life, he wrote France and England in North America, a multi-volume epic including the titles, The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War After the Conquest of Canada, and Jesuits in North American in the Seventeenth Century, in which indigenous people play a central role. The photographs he collected were taken circa 1860-1871 and depict Pawnee, Ottawa, Arapaho, Ute, Cheyenne, and Sioux people.

Photographs by Adam Clark Vroman

Between 1895 and 1904, Adam Clark Vroman photographed the landscape and indigenous people of the American Southwest. His photographs of the Hopi, Zuni, and Pueblo peoples, among other tribes, have been praised for their relatively objective eye; as photographic historian Beaumont Newhall wrote in his introduction to Ruth Mahood's book, Photographer of the Southwest: Adam Clark Vroman, "[he] avoided the sentimental, the contrived, and the obvious. He photographed simply, directly, and sympathetically." Indeed, as the photographs within this web presentation convey, his portraits of Native Americans humanize, rather than romanticize, his subjects. Shown here are a selection of platinotype prints by Adam Clark Vroman in the MHS photograph collection. The platinotype, or platinum print, is known for its non-reflective surface, rich detail, broad tonal range and permanence. The platinum process was patented in England in 1873 and was widely used in the United States and Europe from 1880 through the 1930s, when the cost of platinum became prohibitive and the silver-based processes gained prominence.

Unidentified man metalworking

Unidentified man metalworking

View of Walpi

View of Walpi

People on ponies, at the village of Oraibi

People on ponies, at the village of Oraibi

About the Photographer

Born in Illinois in 1856, Adam Clark Vroman moved to Pasadena, California in 1892 with hopes that the dry climate would improve his wife's early tuberculosis symptoms. Though Esther Griest Vroman died within two years, Vroman stayed on in Pasadena and opened a book, stationery, and photo-supply shop there in November of 1894. The following year, he began his most significant period of photography, traveling through southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico on seven separate trips from 1895 to 1904 to document the area's landscape and indigenous communities. He was often accompanied by his friend, Los Angeles Times newspaper editor Charles Fletcher Lummis, who was also an amateur photographer. During 1897 and 1899, Vroman was employed as a photographer by the Bureau of American Ethnology, (a research unit of the Smithsonian Institution) for two separate trips to the Southwest, the former involving a climb to the Enchanted Mesa in central New Mexico to prove the existence of indigenous habitation and the latter a documentation of Southwestern pueblos and cliff dwellings.

About the Collector

The platinotypes exhibited here have been selected from the Kingsmill Marrs photographs, a collection held by the Massachusetts Historical Society. Marrs, a Boston collector, amateur photographer, traveler, and writer, most likely bought the albums from Vroman at his bookshop in Pasadena in 1901 or 1902. These photographs were taken by Adam Clark Vroman and are housed in two bound albums and are accompanied by a typescript list of all of the photographs they contain, possibly typed by Vroman or Marrs. Most of the titles listed here for each photograph have been reproduced from that list. Other titles have been derived from published captions in books about Vroman's photography by Ruth Mahood and William Webb (see the bibliography, "Sources for Further Research"). Each photograph is also captioned with Vroman's original negative number.

The most complete collection of photographs by Vroman is located at the Pasadena Public Library, where 2,400 of his glass plate negatives and 16 volumes of his platinotype prints are stored. For more information about the Adam Clark Vroman photographs at the Massachusetts Historical Society, please refer to the guide to the Kingsmill Marrs photographs.

Woman identified as Nambaya, molding clay pot

Woman identified as Nambaya, molding clay pot

Two unidentified people free climbing

Two unidentified people free climbing

Man in hat, identified as Oste

Man in hat, identified as Oste

Unidentified family: man, woman, and child

Unidentified family: man, woman, and child

Unidentified woman carrying baby on her back

Unidentified woman carrying baby on her back

Unidentified man in religious garb

Unidentified man in religious garb

Unidentified girl standing with bowls

Unidentified girl standing with bowls

The Wanamaker Expeditions

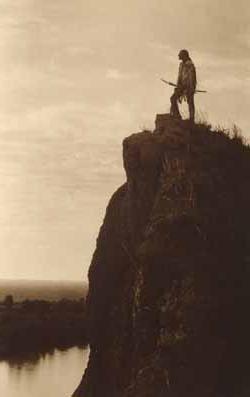

The seven photogravure prints of Native Americans and the lecture program featured here date from the Wanamaker Indian expeditions of 1908, 1909, and 1913.These expeditions were organized and funded by Rodman Wanamaker, heir to the Philadelphia-based Wanamaker department store fortune, and a political advocate for the rights of Native Americans to citizenship in the United States. Wanamaker was particularly concerned that the life and culture of the "vanishing race" would be lost to modernity and relegated to reservation life. To publicize his cause, Wanamaker funded these expeditions to document life and culture through photography, film, and sound recordings.

On each of these expeditions, Rodman Wanamaker employed former Baptist preacher and lecturer Joseph Kossuth Dixon as his official photographer and expedition leader. Dixon had previously been employed by Rodman's father, John Wanamaker, as a lecturer for, and the director of, the Wanamaker department store's education bureau. In his new position with the expeditions, Joseph K. Dixon took over 8,000 negatives of Native Americans, including the photogravures exhibited here. Unlike Adam Clark Vroman's work, Dixon's photographs over the course of these three trips have been criticized for their sentimentality. Through staged shots and photographic manipulation, Dixon emphasized the romanticism of the "noble savage"—a message that clearly complemented Wanamaker's desire to stir sympathy for Native Americans in the hearts of white citizens.

"Chief Tin-Tin-Meet-Sa"

"Chief Tin-Tin-Meet-Sa"

"The Last Outpost"

"The Last Outpost"

"Chief Bear Ghost"

"Chief Bear Ghost"

About the Photographer and the Expeditions

All of the photogravures depicted here are separate prints held by the Massachusetts Historical Society in the Wanamaker expeditions photograph collection. These prints also appear in Joseph K. Dixon's illustrated record of the Wanamaker expeditions, The Vanishing Race: The Last Great Indian Council, which was published in 1913, the year of the final journey. The dates assigned to each photograph in this exhibit thus reflect the date of Dixon's publication; however, the original photographs may have been taken during any of Dixon's three trips in 1908, 1909, or 1913.

Each of the Wanamaker expeditions was organized around a particular conceit that Rodman Wanamaker had chosen as a means to "accurately" depict and preserve Native American life. During the first expedition in 1908, Joseph K. Dixon traveled to the Crow reservation in Montana to film a version of Henry Longfellow's poem, "Song of Hiawatha," using the Native Americans at the agency as actors. He also photographed the Crow people at their camp at Little Big Horn. The following year, Rodman Wanamaker charged Dixon with organizing an "old-time Indian council" at the Crow Agency, a traditional gathering of fifty chiefs from several United States reservations to discuss tribal politics; the last gathering of its kind had reportedly occurred in 1867. As with the 1908 expedition, this "Last Great Indian Council," as Dixon and Wanamaker called it, was recorded on motion-picture film and in photographs. Although Wanamaker's purported aim was to record this inter-tribal tradition, he was determined that it be limited only to chiefs who fit his idea of the "noble savage." As Dixon writes on the third page of the program, "only chiefs of eminent ability, distinguished for honorable achievement among their tribes, as well as for typical racial characteristics" were selected to participate.

During the last expedition in 1913, Dixon organized and photographed a series of flag-raising ceremonies on dozens of reservations across the West, purportedly to show Native American allegiance to the United States and to publicize Rodman Wanamaker's efforts at lobbying for their citizenship.

Sources for Further Research

Online Sources

Finding aid to the Charles W. Jenks carte de visite collection at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Online presentation of illustrations from History of the Indian Tribes of North America by McKenney & Hill hosted by the University of Cincinnati Libraries.

Finding aid to the Francis Parkman photographs at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Photographs of Native Americans, a collection at the American Antiquarian Society, is available as an online inventory with links to 223 images and is summarized on another page describing the collection.

Finding aid to the Adam Clark Vroman platinotypes in the Kingsmill Marrs photographs at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Adam Clark Vroman Collection, 1895-1912 at the Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. (Choose the Vroman Collection from the "Collection Name" dropdown.)

More digitized Vroman photographs can be found via University of California Riverside's arts portal, UCR Arts.

"Wanamaker Photographs and Documents" at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Indiana University.

Printed Sources

Castle, Henry A. History of St. Paul and Vicinity: A Chronicle of Progress and a Narrative Account of the Industries, Institutions, and People of the City and Its Tributary Territory. Chicago: Lewis Pub. Company, 1912.

The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition. "8.37: Ethnic and national groups and associated adjectives." Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Dixon, Joseph K. The Vanishing Race: The Last Great Indian Council. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1913.

Mahood, Ruth I., ed. Photographer of the Southwest: Adam Clark Vroman, 1850-1916. Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie Books, 1961.

Palmquist, Peter E. and Thomas R. Kailbourn. Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide: a biographical dictionary, 1839-1865. Stanford, Cal. : Stanford Univ. Press, 2005.

Sandweiss, Martha A. Print the Legend: Photography and the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Schultz, Duane. Over the Earth I Come. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992.

Webb, William and Robert A. Weinstein. Dwellers at the Source: Southwestern Indian Photographs of A.C. Vroman, 1895-1904. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973.